Table of contents

Getting an FDA New Drug Application (NDA) approved is pivotal to drug companies marketing in the US and marks the culmination, typically, of 12-15 years of work and an accumulated investment in excess of $2 billion.¹

According to FDA, “the documentation required in an NDA is supposed to tell the drug’s whole story, including what happened during the clinical tests, what the ingredients of the drug are, the results of the animal studies, how the drug behaves in the body, and how it is manufactured, processed and packaged.”²

Having a strong data package including extensive product and process knowledge is critical to getting a new drug approved, but by itself may not be enough.

While nothing can guarantee a smooth approval process, it is helpful if the information is presented in an organized and coherent manner – in a way that will be clearly understood by agency reviewers. The ability to do so and to manage the subtleties of interactions with FDA personnel are as much an art as a science and are informed and honed by extensive experience.

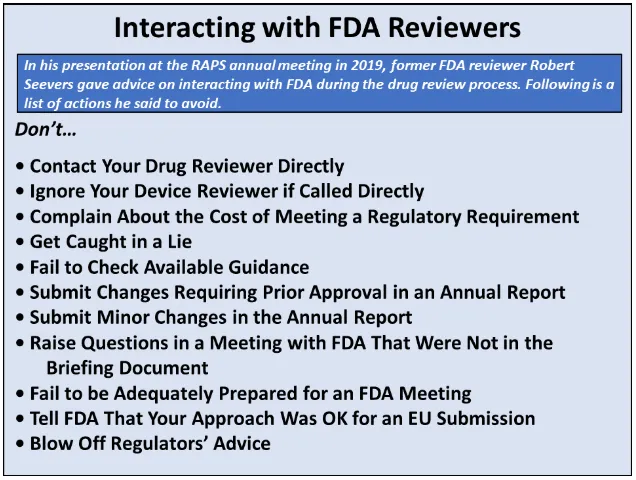

At the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society (RAPS) annual “Regulatory Convergence” meeting held in Philadelphia in late September 2019, Pearl Pathways Senior Regulatory Advisor Dr. Robert Seevers³ shared some of his experiences gained in over 40 years in the pharmaceutical industry, which includes both submitting and reviewing NDAs.

Seevers served for eight years as a Team Leader at FDA responsible for managing a staff of Ph.D. reviewers that evaluated the Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Control (CMC) sections of Investigational New Drug applications (INDs) and NDAs. Subsequent to that, he spent 16 years at Eli Lilly helping lead the regulatory CMC submission strategy for drugs in preclinical development through the NDA and European Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) submission and approval processes for both small and large molecules.

Assuming that a strong, organized data package is being submitted, Seevers focused on other aspects that can be pivotal to a smooth and efficient approval process – specifically, interactions with agency reviewers. He maintained that observing subtleties regarding how to communicate with FDA and how to listen to their advice could potentially save companies millions of dollars by getting a drug or device approved and on the market faster.

Seevers pointed to some specific behaviors to avoid and what to do instead to smooth the review process, which fall into a few broad categories, including:

- Understanding the FDA meeting and review processes and expectations

- Being aware of governing regulations and guidance

- Having respect for agency personnel

- Using the appropriate vehicles for submission of changes

- Using appropriate communication channels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Do Not Contact Your Drug Reviewer Directly

Seevers cautioned against contacting Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) or Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) reviewers directly. He noted that while FDA employees’ email and phone numbers are readily available in the Health and Human Services (HHS) Directory, it would be a mistake to contact them.

“Remember,” Seevers said, “they work in an organization, just like you do. They are not supposed to give advice or recommendations off the top of their heads. It must be vetted by senior management.”

He explained that in the late eighties and early nineties, FDA generics reviewers were caught taking bribes from sponsors to move their proposals – their marketing applications – through faster. “As a result, it was fixed that no one could ever directly contact a generics reviewer. For the new drugs, they have adopted largely the same policy.”

As an alternate point of contact, Seevers suggested working through the project manager, noting that there may be more than one. For example, there can be a Clinical Project Manager and a CMC Project Manager. “You need to find out who they are,” he advised.

“You can call a project manager you have worked with in the past and say, ‘I’m in a different division now, and I don’t know who the project manager or chief of the project manager and staff would be. Can you tell me who that is?’ That’s not going to cause a problem.”

The Project Manager “is going to be happy to talk to you because their job is to move things along. So, you should find a way to contact them.”

Do Not Ignore Your Device Reviewer if Called Directly

Seevers pointed out that CDER and the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) operate somewhat differently regarding review processes. He characterized some of the processes in CDRH as tending to be more informal.

“It is often the case that a CDRH reviewer will call you to ask a question – for example, ‘I am looking for something in your submission and I am not finding it. Can you point me to that in your submission?’ And if you get that call, you should take it. If you get an email requesting a time to call, you should respond. If you are smart, what you will do is say, ‘Can you give me a sense of what you are looking for in this call so that I can be prepared?’”

Seevers reiterated for drugs, “you should not be contacting reviewers directly. For devices, you probably should not contact them directly either, but it would not be surprising if they contact you.”

Do Not Complain About the Cost of Meeting a Regulatory Requirement

Seevers cautioned to not complain to the agency about the cost of meeting a regulatory expectation. “It does not matter how large or small your company is, FDA believes that you have the resources that you need,” Seevers explained.

“This is about public health,” he emphasized. “And if the requirement is put forth on a public health basis, you have to respond in exactly that same way.”

However, it is always ok to ask for an explanation or clarification of the requirements. “If you take one thing away from my presentation this morning, I would like it to be this: It is always okay, it is not impolite to ask, ‘Can you show me where it says I have to do that? Where in the FD&C Act, in the regulations, or the guidances, or just from scientific principles is your reasoning as to why you are expecting this to happen?’”

Seevers noted that he received that question on more than one occasion when he was a reviewer at FDA. “And on more than one occasion, I had to say, ‘Well, you know, you’re right. There isn’t a requirement. I’m going to back off on that.’ It is always okay to ask that. You want to be polite. It is okay to push back on FDA. And then if they tell you, ‘Here’s what it says and yes, you need to do this,’ it is also okay to offer alternatives that will achieve the same public health goal.”

Do Not Get Caught in a Lie

Seevers emphasized the importance of being truthful, not just in the context of actually lying to the agency versus being honest, but also in being forthright, up front, and transparent – for example, involving the agency in an issue when it happens rather than trying to find a resolution before taking it to them.

“When I was working with a client,” he recalled, “they came to me white-faced and said, ‘We just realized that our marketing application is wrong. We said that this drug is a hydrochloride salt. And it does start out as a hydrochloride salt, but we found that it disproportionates, and after time it is not hydrochloride salt anymore, it is a mixture. What do we do? They are reviewing our NDA right now.’”

Seevers recommended an immediate call to FDA to discuss. The client pushed back and suggested it would be better to wait until they better understood the issue and possibly have an answer to present.

He instructed the client to “get on the phone with them right now. We are going to tell them we have a problem. We do not know the answer, but you are going to be our partner as we work to find the answer.” The strategy worked, and the drug is approved and helping people right now.

Seevers noted that there is a huge difference between inadvertently omitting something and telling an untruth. “The word ‘inadvertent’ is one of my favorite words in communicating with FDA,” he said. “We inadvertently left out the stability data. Here it is,” he quipped. “Okay, that is an exaggeration, I have never forgotten the stability data, but you know what I mean.”

He pointed out that if a company is caught submitting falsified data, the FDA can essentially ban the company. They can put the company on what is called the Application Integrity Program. And until you have demonstrated that you have a quality and compliance system that will keep that from ever happening again, they will not accept applications from you. “Can you imagine being a pharma firm and not being able to submit INDs or marketing applications? I have seen it happen. So never get caught in a lie.”

Do Not Fail to Check Available Guidance

FDA provides guidance on a wide variety of topics, and it is always a good idea to check to see if there is guidance on a particular topic before asking someone at the agency that question in a meeting.

Seevers pointed out that in the latest user fee legislation there were commitments from FDA to publish guidance on “a whole raft of topics.” These can be found on FDA’s guidance web page⁴ where it is possible to search for available guidance.

“You do not want to ask a question and have the FDA tell you, ‘Well, it’s right there in the guidance,’” Seevers commented. Noting that some guidance documents are very much outdated, he suggested that it is still a place to start. Most of the guidance that is on the FDA web site has been written or updated in the last 5-10 years.

In the case where an application is submitted without following guidance, if that happens to be for a clinical trial, it may very well be put on hold. If it is for an NDA, the agency might refuse to file. “You may end up getting a Complete Response letter, but you are not going to get approved. So, take advantage of the guidance that is already out there,” he recommended.

Do Not Submit Changes Requiring Prior Approval in an Annual Report

While some of FDA’s actions have associated goal dates for completion, others do not. The Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) created goal dates for FDA, such that the agency must review an NDA or a supplement to an NDA or BLA within a certain period. The 30-day goal date for IND review was previously in place.

However, there is no goal date for the annual report. “And so annual reports tend to accumulate because FDA reviewers are busy,” Seevers explained. “So, they will have a box of them, and one day they will get to that. All of which means some people try to sneak things into their annual report that are more properly submitted either as a Changes Being Effected (CBE) supplement or a Prior Approval supplement.”

He noted that when he was a team leader at FDA, he read through every annual report before putting it in a box or handing it to one of his reviewers, “just to see that nobody was including this kind of change.”

The Senior Regulatory Advisor recommended checking available guidance documents to determine how changes should be filed to ensure they are filed properly. For example, he pointed out, a sterility process change will be a prior approval supplement every time. Other types of changes are CBE.

If after checking guidance documents it is still unclear, he suggested contacting the project manager. “You can say, ‘We think it is a CBE supplement. Does the agency agree?’ You will not only get an answer, you are building a partnership and you are showing that you are willing to follow established guidance.”

Do Not Submit Minor Changes in the Annual Report

Seevers noted that not every change needs to be submitted in the annual report. He cited someone who submitted unnecessarily in an annual report that a new drinking fountain had been installed. Additionally, some GMP changes do not need to be reported – for example, a new pH probe that is like for like.

“So how is this going to annoy your reviewer?” he asked. “You are wasting their time. You are showing also that you do not have a grasp on what GMPs are.”

Seevers suggested using a risk-based approach, asking, “Does this change have any impact on our GMPs? If it does, then it either belongs in an annual report or a supplement. Or could I put this change in a site master file? If I am changing out an autoclave, that is the kind of thing that could very well go in a site master file along with the validation of that autoclave.”

If you are unsure whether it is an inspection issue or a review issue, contact the project manager.

Do Not Raise Questions in a Meeting with FDA That Were Not in the Briefing Document

When you are meeting with FDA, the former FDA reviewer recommended not asking questions that were not included in the submitted briefing document. “They have read through your briefing document, reviewed, met, and worked hard to come to a consensus within the agency on how to respond to your questions.”

If you ask a question that was not there, “that is not fair. They are not prepared to answer it. And so, what you will get is, ‘We’re not prepared to answer that.’ But you will also get some gritted teeth because it shows that you are not understanding the process, you are not being fair to them, and honestly, they will suspect you of trying to pull a fast one.”

To avoid that scenario, Seevers suggested that before asking for a meeting, taking time in your company to brainstorm the questions that you want to raise so that you do not accidentally forget a question. “Narrow that list down. You can only go through so many questions in an hour. I would typically limit it to half a dozen or thereabouts. Stay with those questions.”

“Now, having said that, as the FDA discusses things with you in the meeting, it is perfectly okay for you to ask, ‘Why?’ Remember what I said earlier. It is OK to ask for the scientific, regulatory or legal justification for the agency taking a position.”

Do Not Fail to be Adequately Prepared for an FDA Meeting

Seevers stressed the importance of being prepared for a meeting with the agency, and of practicing. “Whether you are a big company or a small company, the advice you are getting is potentially worth millions of dollars, because it is going to help you get your drug to patients faster or get your device on the market sooner. And so, you want to be sure you are ready.”

He suggested that the ideal way to practice for the meeting is to have somebody play the FDA person, raise issues, and object to the positions you have taken. Decide on who the team is, and who is going to respond to questions on particular topics and address issues in each area. He stressed the importance of making sure that the team members are all on the same page.

Seevers further recommended having one person who is going to act as a conductor. “When I bring a team to FDA, that would be me, and I would say, for example, ‘Thank you for that question about microbiology. Dr. Smith is our microbiologist. I will let Dr. Smith answer that question.’ That sort of thing. Be prepared.”

At the same time, realize that FDA may ask some questions or raise issues that you were not expecting, he explained. “Nobody is perfect, and you cannot think of everything. It is okay if that happens. And if you have an answer, great. ‘Dr. Smith, this is a micro question.’ Dr. Smith can say, ‘Here is how we are approaching that.’ Or Dr. Smith can say, ‘I am sorry, I am not prepared to answer that question today.’ That is a perfectly legitimate answer as long as you finish it by saying, ‘Can I get back to you in a week with an answer?’”

Do Not Tell FDA That Your Approach Was OK for an EU Submission

If you are sitting at the FDA office in White Oak, do not tell them that the EU was okay with the approach you have submitted to FDA. “I assure you that other than at a very high level, the EU and FDA reviewers do not talk to each other. And just because it was okay with the EU, does not mean it is okay in the U.S.”

Instead, as mentioned above, ask for supporting regulation or guidance or scientific rationale – where in the law, the regulations, or the guidances does it say I have to do this? You can use the law, the regulations, or the guidances yourself. Point to where it says your approach is acceptable. Show how ethical issues, science, and public health are aligned with the approach that you are taking.

Do Not Blow Off Regulators’ Advice

Seevers repeated his assertion that a company receives millions of dollars’ worth of advice in FDA review meetings.

“Now, why do I call it millions of dollars? Well, if you are a small firm and you are getting advice from FDA, that is of enormous interest to potential investors or purchasers of your asset or your product. If you have clear advice of how to go from say Phase II to Phase III, which is where it costs a lot more money and most small firms cannot go, your asset is worth a lot more. Probably millions more. So, value that advice.”

Seevers provided an example. A firm had a pre-BLA meeting with FDA. At a pre-BLA meeting exactly what is going to go in the submission and where things will be found are discussed. The FDA gave the firm advice in that regard, and the firm proceeded to submit two weeks later, ignoring every bit of the agency’s advice.

What were the end results? “The FDA official told us not only were they annoyed, they felt disrespected. So, what do you do instead? Accept their recommendations. If you do go in a different direction, be honest about it. Say, ‘We know you said this; here is why we did that instead. Here is the justification.’”

¹ DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RA. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics 2016; 47:20-33.

² FDA New Drug Application (NDA) Information